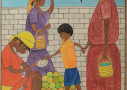

All of the signs are indicative of an Art Renaissance in Haiti. There are over 800 painters on this tiny island, the size of New Jersey. Many are self-taught, working full time, producing in their isolation a variety of styles. Basically primitive, many have gone beyond the early days in 1944 when Dewitt Peters opened the first gallery, the Centre D’ Art, in a place that had never produced an artist.

Unlike music and dancing, which have been a part of the peasantry since the slave days, painting and sculpture were repressed in colonial times along with the practice of voodoo. Painting on canvas has emerged only since 1945.

Only after 1944, the innate artistic temperament of the Haitian found occasional expression in the painted design on a few peasant “cailles” (huts). The first black slaves quite naturally modeled their “cailles”after the thatched huts of their native Africa. This and variations of this simple architectural pattern have endured in rural areas even to now in the form of brilliantly painted doors, shutters and woodwork.

Dewitt Peters, a painter as was his father, had been sent by the United States Federal Security Agency in 1943 to teach English to Haitians at the government Lycee (school) in Port-au-Prince. During the long summer vacation, he discussed the idea of starting an art center with various young Haitian intellectuals who were equally enthusiastic.

Taking the idean to the cultural attaché of the U.S. Embassy, who arranged a meeting with Haitian President Elie Lescot, Peters mentioned a large, private, padlocked house in the enter of the city that might work as a gallery. The President picked up the phone, and the next day the government agreed to pay the rent on the residence which became the Centre d’Art Gallery.

With a small group of more or less amateur Haitian painters, they opened on May 14, 1944, the first show of Haitian painting ever organized in the capital. In a good humored ribbon-cutting ceremony, the President entered the derelict gallery, and $550 worth of paintings were sold the first day.

Restoring the building, organizing classes, and learning how to run a gallery resulted in a deficit for a number of months, until the Haitian government increased the month subsidy to $200, which was matched shortly thereafter by the U.S. Department of State.

Discovery of the Primitives

About six months after the opening, a primitive picture arrived from Cap-Haitien in Northern Haiti. Although not interested in primitive art, Peters bought it for $5 worth of art materials and $5 cash, and wrote an encouraging letter to the artist who had been painting all his life, in spite of the mockery of his friends. His ambition was to record the history of this country in paintings. That was Philome Obin, founding father of the present primitive movement still going on in Cap-Haitien.

Later, on the way back from a trip to meet Obin, Peters spotted the “gaily painted door of a small bar” in the village Mont-Rouis. The painting turned out to be done by a voodoo priest, very poor, but a mystic person with a head of great dignity and beauty. Poverty had forced him into painting houses, but, every now and then, he had done a painting using left-over house-paint and chicken feathers as brushes. This discovery by the Centre d’Art, his subsequent move into Port-au–Prince, and three years of fantastic poetic output before his death in 1948, mark Hector Hyppolite as probably the greatest of Haitian primitive painters.

The Centre produced a market, which in turn gave legitimacy to painting as a profession. Isolated by mountains and poverty, many artists developed their own styles free from accepted rules of famous painters en vogue in other countries.

When tempera and fresco techniques were introduced in 1949 by a co-director of the Centre, Selden Rodman, Bishop Voegeli alone had the faith in the talent of the painters and the “courage to outface the hostility to unconventional art both inside and outside the church” to allow them to decorate the inside of his New Episcopal Cathedral. Today it is one of the “musts” of every tourist. (See Churches – Episcopal pp. 228)

Financial help from Friends of Haiti, encouragement by the government and the growing demand of art galleries in Europe, South America, and, particularly, the United States, have made it possible for artists to succeed in a country with few job opportunities.

In 1950, a group of dissident painters left the Centre to form their own gallery—the Foyer des Arts Plastiques, and except for a few small galleries founded by individual artists, most good paintings found their way to the six principal commercial galleries.

The Cap-Haitien School of Primitive Art is quite different from the traditional western styles ranging from impressionism through cubism.

The danger signs of the so-called “Coca Cola” civilization plus a growing tendency of some galleries to encourage copying of “saleable paintings”, will eventually cheapen both the artist and his work; but the art has improved immensely, and has been discovered world wide.

If someone had predicted in the 1860’s that a new style of painting called impressionism would less than 150 years later sell in the largest galleries and auctions of the world for millions of dollars, would anyone have believed it or bought one for a few dollars? I believe that in the field of primitive painting a similar opportunity exists with Haitian art today.

Represented here are biographies and paintings of 800 Haitian painters ranging from excellent or high price (*****), to very good (***), to mentionable. This collection, by the Franciscus Family is perhaps one of the largest and most complete to be assembled to date outside of Haiti. The selections were made with the help of all Galleries mentioned above and upon advice of their curators and various collectors, the classifications by stars, was created as a value guide to newcomers.